Dear Tomorrow Kieran,

Myrtle Beach in January was a horrible idea.

Mom and Dad swore that Connor loved it as a child, but even in his youth I can’t ever imagine my brother willingly going outside. I wonder what he thinks of the beach now.

Didn’t matter, he was stuck here for eternity regardless. Here, amongst the snowbird retirees and perpetually gray skies.

Today, standing at the edge of the ocean, I was reminded of a scene that had unfolded here over a decade ago: Connor, wielding a half-dead crab skewered on a piece of driftwood, chasing Elisa through the crashing waves, tears of pure terror streaming down her cheeks. Even after turning eighteen last year, their relationship never improved much. The echoes of her screams in my memory still rattle my spine.

I found another crab as I walked along the beach today. Rather, I found a shell, with no signs of movement inside. It lifelessly crashed over and over again on the sand, the tides tossing it back and forth across rocks and debris, as if whatever force had killed it wasn’t satisfied. My brother was nothing more than that crab now. His ashes were scattered on the shallow ocean floor, helpless to the whims of the tides, food for the low-lying mollusks.

Elisa had refused to touch, or even go near, the urn. I couldn’t understand why. All of the blood, dirt, broken glass, and pieces of the I-93 asphalt we had seen on Christmas Eve in the coroner’s office had been washed away; he was forged-by-fire bone dust. My mother had stood ankle deep in the water, extending the urn to her, silently begging her with bloodshot eyes to say one last goodbye to the boy she had preceded in birth by mere minutes. Elisa just shook her head.

Dr. Garrett isn’t allowed to talk about her other patients. If she was, I can only imagine the things I’d learn about my sister. I know she has to write these letters too; maybe I’ll get to read them someday.

I had a dream last night. I finally figured out that that’s what it was. It was the second time in my life. The only other time – a few nights after Christmas, the first time I’d slept after seeing Connor’s face for the last time – I had panicked. Thought I was hallucinating, that I was going crazy. When I heard others discuss their dreams, I had assumed it was a figure of speech. But in the dead of night, I saw Connor’s face, blood trickling from his hairline and into his eyes. He wasn’t so much staring at me as he was staring through me.

Last night, I was sitting at a piano in an empty concert hall. Empty, save for Connor, sitting front and center in the mezzanine. I was playing Liszt’s First Transcendental Etude, the Preludio, sailing through the same right hand arpeggios that I was painstakingly stumbling over the night we got the phone call. He held his trademark blank gaze, giving me the slightest nod of approval as I struck the last chord.

The thought of sleeping tonight is making me sick to my stomach. As long as I’m awake, I can control what I’m seeing. I can drown out the visions of my brother’s face with the soft sloshes of the low tide, with my parents’ hushed arguments from across the hall. Who can say what the depths of my mind will conjure up given my newfound creative ability – I’m unwilling to learn the answer tonight.

Dr. Garrett wants me to finish each of these with a hope for tomorrow. So here: I hope by the end of this week, I’ll know my brother better than I did this Christmas Eve on the autopsy table.

Yesterday Kieran

—

Dear Tomorrow Kieran,

Elisa got up before dawn this morning – or maybe, like me, she was still awake. I found her leaning against the rail of the balcony, thumbing through each link of her chain bracelet. I read once about the five stages of grief, but I don’t think she will ever move past anger.

Still, I saw the glimmer of wetness on her face. Her nose was scrunched, and her eyebrows were crinkled together. Connor had told me this was the avoid Elisa signal. He learned to read her expressions long before I did. Maybe it was a twin thing.

I don’t get it, she said upon noticing me behind her. We hated each other. I shouldn’t even care. But he knew me. Maybe better than anyone.

I can’t imagine ever wanting anyone to know me.

I can’t imagine ever wanting a human being to know that as I stood here, in a house full of my family grieving my dead brother, that the only thing I felt was the fear of my own mind.

I offered nothing to Elisa but silent company.

Mom and Dad were awake within the next hour, and things were already going to shit. Connor’s obituary was released today, and according to the pitch and timbre of my mother’s voice, something had gone wrong. Apparently, my dad had submitted the wrong picture; no, David, you were supposed to send them the one in the blue polo where he actually looks like he’s somewhat smiling, not this one where he looks like a fucking psycho, how could you be so stupid, this is how our son is going to be remembered forever.

I looked up the article, and I saw the photo in question. He looked just as I had remembered him.

Only his face was in frame, but I remembered the entire family photo. It was five or six years ago, and I stood side by side with Elisa, copying her bright eyes and slightly crooked smile. Even at this age I had mastered the art of taking on her personality as my own. Through the years she spent with me avoiding Connor, I had picked up on all the little things that had given her the three-dimensional identity I so desperately sought. I had no interest in the piano until my parents decided to enroll her in lessons. She quit only six months in, but I continued – it gave me something to call my own.

As time went on, I found others to fill her role. I suppose Liam and Sebastian would call us friends, and Sophia would call me her boyfriend, even if the only criterion I met was proximity. As far as I’m concerned, they’ll never know the true purpose they hold in my life. I took their mannerisms, their speech inflections, their interests, their expressions. They’re full-time teachers, and oblivious to it.

Last week, Dr. Garrett asked me if I had ever been in a romantic relationship, and I told her I hadn’t. It wasn’t necessarily a lie. People in real relationships were willing participants. Their skin didn’t crawl the second their significant other touched them. They didn’t fear an inevitable phone call, where they’d be forced to carry on a conversation without the crutch of mirroring their girlfriend’s body language to feign interest in what she had to say. When Sophia asked me to homecoming in the fall, it was just easier to say yes. No dramatic rift in our mutual social circle, no questions as to why she wasn’t good enough for me, no disappointing her. My brother disappointed people. We were nothing alike.

My mother’s voice had now risen to its full volume, and I could hear her tears begin to make their way into her words. I was sitting cross-legged at the edge of my bed with my hands over my ears when Elisa appeared in the doorway.

Up for a swim?

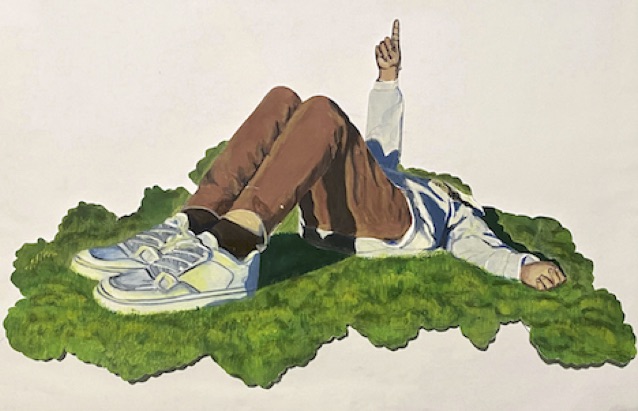

She knew I couldn’t swim. Yet she had now latched onto my wrist and was dragging me out to the beach. This was the Elisa I remembered. This was the light, the spontaneity that convinced me to skip school to see the first snow of the season from the depths of the New Hampshire woods, that got our closed-off father to sing karaoke at her birthday party. She would never know what it was like to have to plan her every word and action.

I shivered as the wind threw frigid ocean mist against my bare arms. Elisa seemed completely unfazed, sprinting past me and diving headfirst into the waves fully clothed. She waved me over with a bright smile.

As I stepped into the icy water, I was overcome with the realization that the remains of my brother could be beneath me. He was probably long gone now, pulled by the currents past the drop-off point and into the vast depths of the Atlantic. I shuddered at the thought. I suppose I could swim if I needed to, but the idea of my feet not touching the floor – and not knowing what lay beneath – horrified me.

But Elisa is a natural-born swimmer, signed to UMass for this fall. Whatever gene had given me the handspan necessary to master Rachmaninoff had given her long and muscular limbs, and despite her seemingly endless list of talents, she dedicated her life to her athletic career. She kept moving further and further from the shore, calling me out to join her. Now waist-deep, I shook my head and copied her smile, crossing my arms the way I’d seen her do countless times. She gave up trying to persuade me and swam back to the shore.

She glanced down at the sand, then back up at me.

You think jackass has been eaten by the fish yet?

I stiffened. Her tears this morning, her lively tone now – it was throwing me off. I tried to analyze her expression, but I had never seen her like this.

Oh, relax. He’s been dead for three weeks. We can joke about it now. You can drop the whole gloomy artist thing.

This wasn’t her joking face. There was still a weight to her words. I couldn’t match it.

She leaned back with her eyes closed and sprawled out on the surface, floating delicately with the rhythm of the low tide. As the wind drifted her out, I kept my feet planted firmly in the sand, where I could see the bottom, where I knew the merciless ocean didn’t have the upper hand. I was in control as long as I could stand.

It wasn’t as if I was so torn up about the whole ordeal that Elisa’s levity had offended me. But there in the water, I was all too aware of the ground on which I stood. The water felt even colder with his presence. And while I couldn’t force myself to grieve, the least I could do was to try my best not to desecrate his honor, or lack thereof. Otherwise, I was no better than him.

If it were me, Connor would have laughed, and thought nothing of it. I told this to Elisa.

Her response was a single word: psychopath.

She launched into a series of anecdotes from our childhood, some I was familiar with, some I wasn’t. Her nose was scrunched again, and she vigorously spat out her words, whatever peace the ocean had given her vanishing. Connor had cut out a chunk of her hair while she slept the night before their first day of high school. He’d fed her beloved hamster to a garter snake in our backyard while she watched. He’d spread rumors about her sexual escapades so vile they got a teacher questioned by the police.

When Connor told me these stories, his voice had brimmed with pride. If you keep them laughing, he told me, they’ll never ask questions. Keep making them smile and they’ll never ask why you can’t cry.

I suppose that Elisa had finally achieved whatever catharsis she sought out there, because she pulled me by my elbow out of the water and led me back to shore, curling up next to me on the dry sand. She laid her head on my shoulder, and I could feel her softly shake as she fought to hold back tears. For years we’ve sat in this exact position, her wishing that our parents would do anything to stop him, pay any attention to his obvious problems, that they’d send him away, that they’d know that she wasn’t safe from him at home or at school. I’ve never been able to help, to offer advice, to even empathize, but I’ve always been the only one she had that would listen.

I don’t know, she said, as if she could read my confused thoughts. I just knew that even though he was awful to me, that in some fucked up way it was because he loved me.

I’m not sure if it would help her to know that he didn’t.

He wasn’t capable.

The closest thing he had to love was whatever weird sense of pride he felt towards me.

Whatever he saw in me that, even before I could form complete sentences, told him I suffered from the same fundamental lack that he did. I guess, in a way, it was comforting to have him around – compared to him, I was an upright citizen. Without him, I’m more exposed than ever. I’ll spend my whole life wearing Elisa’s identity as a costume, but I’ll be discovered eventually.

So, there I sat, arm around my sister, lying to her, telling her the brother we both hated truly did love us, praying to whatever powers that be that she’d never know the truth. Even if I knew my brother was out there, seeing right through my disguise and laughing.

I’ll never know what it’s like to feel the way Elisa does, but I hope she finds her peace.

Yesterday Kieran

—

Dear Tomorrow Kieran,

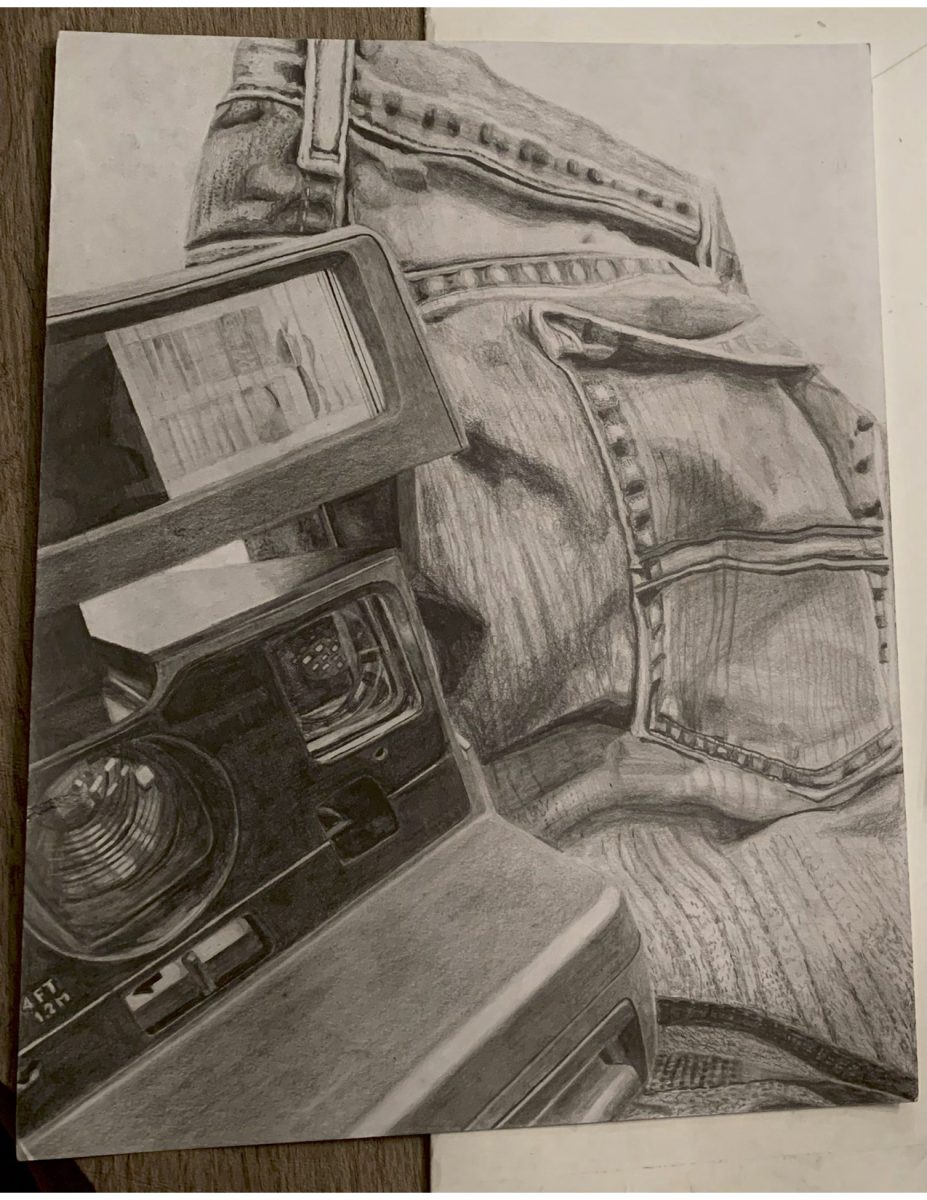

There’s a Steinway in the basement of this hotel.

It’s been three weeks since I last touched a piano, and the joints in my hands and wrists have been growing stiff. With each passing day, I imagine my technical prowess draining out of my fingertips, and I become more and more fearful that returning to practice will remind me that my Preludio would never be as clean as it was that night in my subconscious.

But this morning, I woke up from my first sleep in days, sprawled on a folding chair on the balcony, to my mother’s hand softly resting on my shoulder.

There’s a piano downstairs. Play for me?

I nodded.

No Liszt.

Why not?

Too fast. Play something nice.

I can’t recall the last piece I played that wasn’t Liszt. In fact, I can’t imagine a work better than those written by the greatest pianist to ever live. His compositions weren’t so much melodies as they were displays of pure athleticism, demanding grace, precision, speed, and at times, brute strength from their performers. I could spend weeks working up four measures of one of his etudes to concert tempo, focusing only on the gauntlet of notes before me. I could get lost in the staggering difficulty. Liszt left no room for thought in his writing.

Left by the previous pianist was a battered loose leaf of Chopin’s Prelude in D Flat Major. I had heard this piece once, years ago, on a cassette my teacher had given me. My memory of the prelude was the A-flat; despite the continuously changing melody, the A-flat was struck with every eighth note, giving the same sort of relentless monotony as a leaky faucet.

I began to read. The Transcendentals made this piece look like child’s play in comparison, and the key signature fit seamlessly into my hands, with my fingertips resting delicately on each black key. My rendition was note-perfect. But this repeated pitch, this drone – it didn’t sit right with me. Something about it was grating; its incessant pounding made my stomach turn. It continued, unaffected by the shifting tonal center and chord context, completely self-serving, as if without regard or care for the piece of music it belonged to, until the piece was over. And then it just…stopped.

Connor was staring at me.

I frantically glanced around the room, down at my hands, back at the manuscript. He wasn’t here. But I could sense his empty gaze on the back of my neck. He had me surrounded. He was in my brain. I started the piece again, but Chopin couldn’t distract me the way Liszt could. There was too much empty space, too much room for Connor’s voice to be heard between A-flats. My hands had begun to sweat, and my vision had blurred to the point that the sheet music before me was a solid black line on top of the bass staff, as if it were an EKG denoting cardiac arrest.

My fingers slid off the keys and clutched my chest as I struggled to breathe. My mother’s hand was once again on my shoulder, and she pulled me into her side as I shook violently. I gripped the fabric of her sweater, choking on air. He was gone. I felt my heart rate slow. She looked at me with a tilted head and a slight smile. This was a look she’d given to my sister countless times, but never to my brother.

I’d seen it once. I was in New York taking a masterclass at Juilliard that was to serve as a primer for my pre-college audition, with an adjudicator known worldwide for his brutality in addition to his virtuosity. I had just finished an excerpt of the Friska from Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, and I awaited his compliments, knowing I had played with technical perfection. I locked eyes with my mother in the audience, and she smiled. My brother could never make her this proud; we were nothing alike.

I heard all of the notes, the adjudicator said, but felt none of the joy.

I froze.

Liszt gave you a masterpiece, and you’ve neglected its beauty.

I left the recital hall with a racing mind and chattering teeth. He’d seen through me. Torn my mask off and exposed me to an audience. Shown all of New York City the passionless, apathetic freak I am. My mother chased after me, spouting some bullshit about how I shouldn’t let one man’s opinion discourage me. I didn’t tell her he was right, and I certainly couldn’t tell her that seeing her smile after my performance was the most like a human being I’d ever felt.

I continued playing after that day. My family saw it as a bold act of defiance; I saw it as it always was – a distraction, and a damn good one. As long as I was studying, I didn’t have time to contemplate my own existence, and from the outside, I was just a passionate artist.

I felt like a human again today, but this time, I was a scared, powerless child. Yesterday, I thought that as long as I was awake, I was safe from you, I was in control. You’ve ruined that for me. You’ve ruined the fucking piano for me. What could you possibly have left to tell me?

I hope you’re happy.

Yesterday Kieran

—

Dear Tomorrow Kieran,

There was no ice on the I-93.

These past few days, we’ve been able to escape everything back home. We’d taken Connor and gotten the hell out, and nobody – save for a few highway patrol officers and medical professionals – was the wiser.

Now, the world knew he was dead. Died in the late hours of Christmas Eve, leaving behind his parents, twin sister, younger brother, and Golden Retriever. No elaboration was necessary; everyone that had ever cared about him already knew before the obituary was printed. Why should it matter how he died?

Bedford’s not big enough a city for the law to stay objective. When your cousin’s neighbor is dating a highway patrolman, for example, suddenly dashcam videos aren’t so confidential. Words spread. You learn that there was no ice on the I-93.

I can’t remember the last breath I took that wasn’t shaky and labored. I spent last night at the kitchen table, meticulously tapping out the arpeggios of the Preludio. I couldn’t go back to the piano; you were there. If I could hold my focus here, not give myself time to think, I couldn’t hear what I knew you were saying.

Fear isn’t an emotion – I know because I can feel it. For as long as I can remember it has run like heroin through my veins. It’s the closest thing I have in this world to a friend. It kept me going, kept me in check when I relaxed too much and my cover began to slip. But now, it has become debilitating.

I was still at the table this morning when Mom finally left Elisa’s room – she hasn’t shared a bed with Dad since our first night here. She met my gaze immediately, barely breaking eye contact as she pulled out the chair next to me. She set her hands on top of mine, ceasing my anxious tapping, and that’s when she told me that Connor had killed himself. That there was no ice on the I-93 on Christmas Eve. That the dashcam video hadn’t shown a possum or a squirrel run into the road, that he had hit the overpass at seventy-two miles per hour straight on.

He was obviously depressed, she told me. Depressed, and hiding behind a cold, unfeeling exterior. She always knew there was something wrong. She could see the void in his eyes from the moment she held him for the first time. She should have known. She did know. My father was too goddamn stubborn to send him to therapy. It was his fault this happened to Connor. Now he won’t leave their room. Which is good. He should stay here and rot in his own guilt forever and she’ll take me and my sister back to Bedford and we’ll forget about all of this.

Her head collapsed into her elbows with a massive sigh. She didn’t mean that, she tells me.

Whether it was the shock or the sheer mental exhaustion, I didn’t attempt a response. Just stared at her. If she did look up, she’d see that same void in my eyes, and she’d lose her only hope, that I was the replacement for her broken firstborn son. My fear had run out of energy. I couldn’t care.

She looked up. She had finally seen me for who I was.

Why won’t you cry for him? He loved you more than he loved anyone.

For the first time in my life, I spoke without consideration. My mask was falling.

No he didn’t.

She recoiled. How could you say that? I knew it was a question, but she delivered it with a flat tone of resignation.

I couldn’t stop. I was falling down a hill, and God knows where it would end.

He didn’t love me, he didn’t love anyone. And maybe…

These were not my words. You were forcing them out of me. You were watching from beyond the veil and laughing as you made me break our mother’s heart. But these last ones…I choked on them. These were the words I had spent sixteen years running from. I knew we were tied together by this plague, but something made me believe I wouldn’t turn out the same. That I could make people feel something other than disappointment and heartbreak. I couldn’t bring myself to voice them, but they rang like a gunshot in my head.

Maybe I’m just like him.

I didn’t have to say the words out loud. My mother said them for me.

I sat there and I let the wave come. I let myself become her method of catharsis. I deserved it. I absorbed every word. Freak. Psycho. Machine.

Elisa had been beckoned by our mother’s shouting, and now she stood over the far end of the table, begging, pleading her to stop.

If the rest of the world has to know who I am, so be it, but for God’s sake, let Elisa be the only one that can’t see through the disguise. Give her that grace.

I was Connor’s opposite, she was saying. I was all the things she wished she had in her twin brother. I had always been there. I pulled my legs into my chair and wedged my head between my knees. I couldn’t take it. As much as I wished they were true, Elisa’s words hurt more than my mother’s.

And maybe that’s where we are different. Maybe I hoped every day that I’d find something that would elicit any hint of emotion from me, and you were perfectly content to feel nothing. Maybe I made every effort to look as if I cared for my sister, and you didn’t mind that she hated you.

But did it matter?

We would never love, and we would never feel loved. We’d never get anything out of the world, and we’d never contribute to it. The outcome was the same. You knew that. You knew your fate and you decided to take things into your own hands. You were right. That’s why you’re here. You want me to know that there’s an easy way out. You tried to give it to me.

But there were things you’d never seen that I have.

I’ve seen packed recital halls light up at the end of my performances. I’ve seen my sister laugh at my offhand comments. Was the joy fake if I could see it in other people? Was it worth it to keep going just to continue my lifelong ruse?

I know you’ll tell me, whether I’m ready to hear or not.

Kieran

—

Dear Connor,

It’s fitting, isn’t it, that your “celebration of life” was so gray. For someone who was loved and couldn’t reciprocate, for his family’s final goodbye to be met with bleak skies.

We’re over New York City now, and Mom still hasn’t released my arm from her iron grip. I can’t say what will become of her when we get home, but I assume I’ve given her enough of a scare that she won’t leave my side for a while.

In the seat in front of me, Elisa glances over her shoulder, as if to ensure I haven’t fallen out of the window. She’s done this about once every ten minutes since we took off. I give her a slight smile. It’s the least I can do. You and I have really put her through the wringer this week.

And last night.

Last night, after you spent the day tearing what was left of this family to shreds, you accompanied me to my dreams. Over and over again you turned over the ignition. Over and over again you pulled out of the garage, a stray bulb on a string of Christmas lights scraping your antenna. Over and over again I heard you invite me to come along in the passenger seat. And as I startled awake last night, I wished that on that night three weeks ago I’d said yes.

You had unfinished business with me, but you were gone the second I opened my eyes. You were going to make me find you. Luckily, I remembered where we’d left you.

With my family having borne witness to my internal atrocity, I had nothing to fear in something as trivial as the ocean. I tore across the sand and into the water, paying no mind to the footsteps behind me, my splashes echoing along the silent midnight coast.

I felt the sand beneath my feet slope downward into oblivion, but I pushed farther. I gave you all the power. You decide. If there’s a life for me out there, carry me back to shore.

The frigid water was stiffening my joints, and my legs were struggling to keep me afloat. I could feel the sting of saltwater trickling down the back of my throat as I gasped. You were making your choice clear, but I had failed to consider the footsteps.

Elisa had latched onto my wrist. She was kicking furiously, slicing through the water with one arm, pulling me like a rag doll until my knees scraped the dry sand. She hit me between the shoulder blades until I started coughing up seawater, all the while berating me. You absolute dumbass. You know you can’t swim. She pulled me into her side, cradling my head as I shivered. How could you be this fucking stupid. It’s the middle of the night. What the hell were you doing. I smiled.

To tell you the truth, I don’t think you ever made it to Myrtle Beach. If you did have a soul, if it does walk the earth, it is being blown back and forth by semis along the I-93. Maybe it’s a testament to our similarities that I mistook my own stream of consciousness for your ghost.

For years, you and I have been lost. We’ve been specks in a sea of billions of people we’d never understand. I wish I’d known years ago that we were stuck there together.

I don’t think I’ll ever know why you had to die. Were you depressed? Was depression a persistent negative emotion, or the complete lack of feeling? Why was your death necessary for me to finally live? Elisa will never look at me the same way. But even now that she knew I had spent my entire life faking emotions, she got to bear witness to my first real one. I wish it hadn’t taken the death of one sibling to finally know the other.

Maybe tomorrow, I’ll sit at the piano, and I’ll take my time moving through phrases. I’ll look at a picture of the ocean and not wonder what lies beneath. I’ll speak to my sister without planning every word. It will take time. But now that I’ve begun to grieve, I may actually heal.

Wherever you are, whatever you’re doing, I hope that that feeling you sought on Christmas Eve, that promise of escape from perpetual darkness, you’ll find in me.

Love,

Kieran