There used to be animals in the desert. Rabbits with ears as broad as cactus leaves. Wolves that prowled the night. Snakes, fat and twisted, curled under rocks or around the broken posts of Mayor Annering’s front porch. In the evenings, children just like you would run into the hills, chasing tarantulas the size of their heads.

The animals fled when the water fled, two years ago. They either fled or they died. You are lucky you were too young to remember the carcasses, littered by every roadside and behind every scraggly bush. You are still too young to be wandering the desert in search of bones, so listen when your parents tell you to stay close.

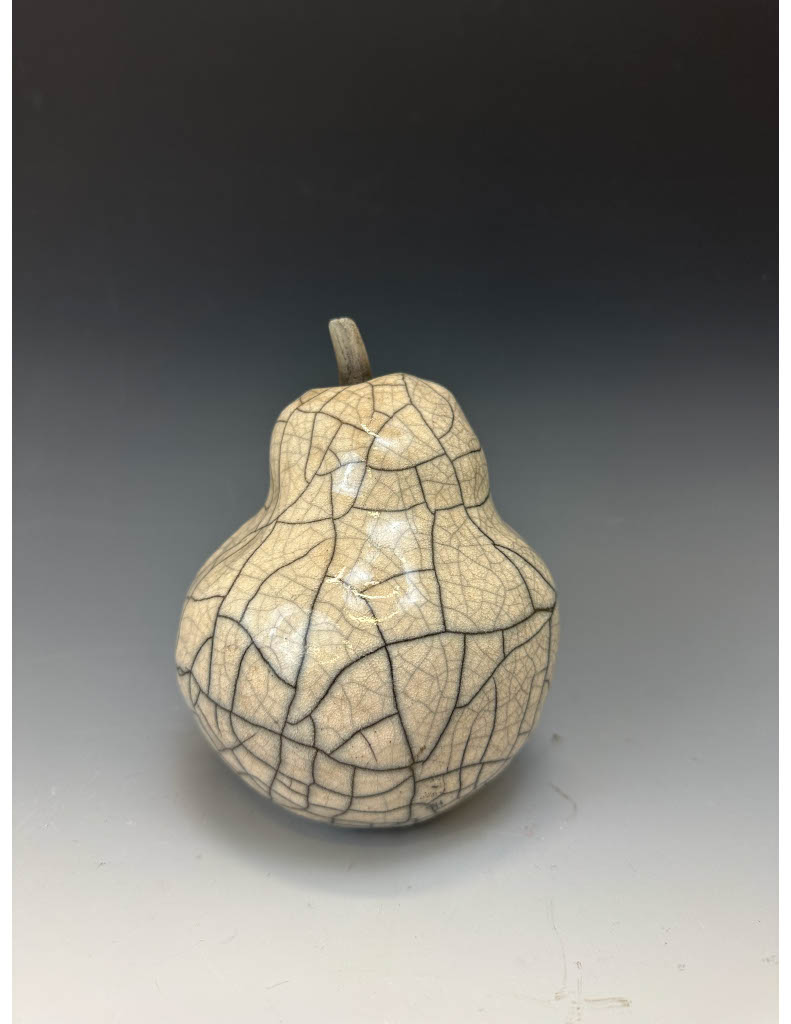

The story I have for you today is not about animals, but it is from the time just before the animals disappeared. This is a story about our town. It is a story about me, and about my daughter. Her name is Mada. She is not here with us, but I am sure you have seen her statue in the schoolyard. I will tell you a secret—the clay molders never got her nose right. They made it slim and soft, to be more fashionable, but Mada has a nose like a stubby stick. Her brow is as wide as the statue’s, though, and her arms were always braced in that unnatural way—tightfisted, pulled behind her.

One day, one day soon, she will come walking back through the town gates. She will be older and stronger, maybe hard to recognize at first, but I would know her coal eyes anywhere. Dust would cake around her brown ankles like it used to. And she will lead the way to a world where there is water like there is earth, and sun, and sky.

—

When Mada left, she was seventeen years old. The morning was cool and cloudy, one of the last days we ever saw clouds in the sky. I believed it to be a good sign. Mada was going to find water, and the clouds would show her the way.

All of the town gathered in the square: farmers on break from plowing hopelessly dry earth, miners fresh off the night shift, families with their toddlers and newborn babies—you—clutched tightly against them. A wide circle was left around Mada; we knew she liked her space. Mayor Annering gave a short speech about bravery, sacrifice, hope… I watched Mada, and I cried.

Mada is not the kind of girl you cry for. Some children you coddle and soothe, but Mada possessed a deep aversion to sympathy that I never understood. She was not a difficult child to raise—she did what you asked—but she cared very little for praise, or comfort, or any manner of affection. I did not want to cry for her that last day. I had remained expressionless as she left on so many past expeditions. But she was leaving alone this time, without the hunters who typically accompanied her, and she was going far away, in search of some distant land none of us could even dream of.

The night before, Mada and I had sat close to the fireplace, quiet. She hooked her little finger through mine, and there was a calmness about her, like all the swirling sand and silt of her had finally settled into the solid layers of a mesa.

Are you afraid to go? I asked.

No, she said. Yesterday, I was in the desert and a fox asked me if I wanted to borrow his ears. I put them on, and I heard a thousand pebbles of water hitting the ground, all at once.

Rain, I said.

Rain, she replied. The fox told me about rain. She smiled at me, wide-mouthed and crooked-toothed. I cannot wait.

I covered her hand with both of my own. Just come home safe.

You know. A speck of ash fluttered from the fire, and she watched it settle on the arch of her foot. You can still come with me.

I squeezed her fingers. I am too old. You are going alone so you can travel faster, not so I can slow you down.

She frowned. Still. And then, hesitantly, Thank you for being my mother.

I pulled away. Of course.

She scooched closer to the flames until her knees brushed the brick platform upon which the fire roared. To the light, she whispered, The desert fox runs and runs and runs. She sleeps in the bushes, and when she wakes up, all the other animals are gone.

The next morning, I watched her small shadow disappear into the horizon, lumpy with supplies. She did not look back.

—

My favorite memory of Mada is from the annual Summer Festival, when she was fifteen. Back then, the Summer Festival was a true celebration: many towns gathered, competitions of javelin throwing and pottery making, meat and fruit heaped in piles. Children wandered in packs, playing games together and dancing the traditional dances in pairs.

Mada went alone. She preferred to do things alone, despite my offer and the offers of a few others to accompany her. At the festival, she flitted from spectacle to spectacle, always at the edge of the crowd. With her hair braided and an orange skirt billowing behind her, she was barely recognizable as Mada the Water Finder, Mada the Hero. I would catch glimpses of her throughout the night from my seat by one of the bonfires. Once, a little boy grabbed a fistful of her skirt, stopping her. Mada stared down at him for a long moment, then crouched and whispered something close to his ear. I do not know what she said, but the boy let out a gurgling laugh and waved his arms.

A parade of jugglers crossed in front of me then. When they cleared, Mada had walked away, but the boy remained: his mother was scolding him, while in one hand he clutched a string of beads. Mada must have gifted him the beads—I had seen her put them on that morning.

The boy soon passed away from fever, otherwise he would tell you this story himself. I tell it to you now because that is what I love best about my daughter: her kindness. It is hard enough to be a hero, but not every hero is kind.

—

When Mada was thirteen, she tried to explain how she found water. Her thirteenth year was the year she quit school, too busy leading expeditions to keep up with class work. In an effort to occupy her during the awkward half weeks between her trips, I asked her to explain everything, from the color of the dirt to the noise the owl made at dusk. She entertained my questions once in a while.

You have dreams, right? Mada said. She sat on the side of her bed, her knees and toes dangling over the edge. Her cheeks were chapped from the sun, and I made a note to pack a hat for her the next time she left. It sometimes felt like I spent more time missing Mada, more time preparing for her absence, than I spent raising her.

Of course, I replied.

She never spoke in-depth of her adventures in the desert, what she thought of wandering in the wilderness with only adults for company. She merely told me of the sights she saw: mesas as wide as the sky, tumbleweeds on top of cacti, rocks in the shape of a human fist. What do you dream of? she asked.

I took a moment to think. My mother and father, who have passed on. My own childhood. Thirst.

She chewed on her bottom lip, then said, You dream of things you know.

I suppose.

Most days, it feels like the only thing I know is finding water. So I get ideas, and I dream about them, and sometimes my ideas are right.

There were people in town who considered Mada a spirit of some sort. She got looks in the streets. We did our best to ignore them, but it could be hard.

Don’t tell anyone you learn of water through dreams, I said. I could only imagine the reactions from the neighbors.

Mada rolled her eyes. Of course, she said. I know better.

—

Mada completed a total of one hundred and eighty-two water runs for our town before her final journey. The expeditions were anywhere from days-length to two weeks, and she always returned triumphant. She led the way into the desert, barefoot and silent, a wolf on a scent trail. Wolves have much better noses than ours, and Mada had a wolf’s nose for water. She knew which cacti to cut open, which boulders sheltered shallow pools, which soft patches of dirt to dig below for well springs. Our water supply today, that all comes from her.

She only came home empty-handed once. She was younger, maybe eleven or twelve. As the four hunters who had accompanied her guzzled water in the square, Mada sat in the shade of Mayor Annering’s porch and scratched patterns into the earth. She did not look up when I approached.

Did you drink anything? I asked.

She nodded and patted the water pouch strapped to her chest. I had a little left.

What happened?

She shrugged.

Mada, what happened?

I don’t know.

You have to know. Is there no more water in the desert?

She drew a braid of hair and then a tangle of squiggles around it. There was silence for several moments, and then she said, Nobody wants to go to the Summer Festival with me.

I sighed. This again? Mada, you are welcome in any group. What about the friends you went with last year?

No! Nobody wants to go with me!

I squatted next to her. That’s not true. Everyone loves you. They love you because you are talented and smart and wonderful.

Across the square, Mada’s classmates filed out of the school hut and separated into play groups. We both leaned back when three boys ran so close by us that I could taste the dust thrown up by their bare feet. They turned briefly to see if I would chastise them. One of them pointed to Mada before all three sprinted away.

Do you want to go to your class? I asked.

Her eyes were fixed on the ground, bright with loathing and bright with tears. Can you leave me alone?

I threw up my hands. Mada—

I’ll find the water next time. I promise.

I left her alone. She grew moodier the more she was pressed, and at times it was best to let her disappear into herself.

Mada missed a lot of town life for her expeditions. Those early teenage years must have been hard for her, observing so many relationship rhythms that she could not follow. When she was younger, she would ask me for summaries of the happenings—who was friends with whom, and what had been decided about this small crime or that marriage proposal—but she gradually stopped. I assumed she lost interest.

That night, Mada did not come home. I fretted until sunset, then ran to sound the alarm at the Mayor’s house. People peered drowsily from their doorways, sated from dinner and bundled in blankets against the oncoming chill. Whispers circled—Mada was gone, Mada had run away. The Mayor told everyone she was simply missing, and an effort must be made to find her at once. Neighbors dispersed, most heading straight for the desert. A few surrounded me with questions: Was I sure she was gone? Could she not merely be hiding? She liked to be alone; she was a strange girl with strange habits of coming and going.

By midnight, there was still no sign of her, and a true sense of urgency washed over the town, as bleak and lurid as the blue light of the rising moon. What would we do without Mada? I paced the length of the square five times, ten times, fifty times over, trying to control my breathing. I had checked the underside of every hollow porch and step, the crevices between houses, any dip in the sand large enough for a child to curl into. I imagined her lost in the night, caught in the jaws of a snake or a large cat. Only in the brief lapses of silence between harried cries—Mada! Mada?—did I dare consider that she had left on purpose.

Did she not think she was loved? Had I made her feel so horrible about returning empty-handed that she did not want to come back? She was so young—it was easy to forget, with the way she slung responsibility like a pack over her shoulder and carried on. When was the last time I had asked if she was happy?

Mada! Mada, where have you been? Commotion erupted at the western end of town. I pushed through the crowd, a hand clutched at my throat.

Mada! I cried.

And there she was, so slight, an ancient apparition, weighed down by the three water pouches strapped to her back. When I stepped before her, she met my gaze with an earnestness that weakened my heart.

I found water, she said. She dropped the pouches by my feet. I grabbed her around the waist and pulled her tight into my chest.

Never do that again, I hissed into her hair. Oh, Mada. Mada.

Others pushed into us, patting Mada’s head, holding her hand. The water was quickly collected to be poured into the communal storage. In the warm muddle of attention, Mada’s body relaxed a fraction. I rubbed her arms, trying to dissipate the cold of her skin, and she did not nudge me away. When Mayor Annering knelt before her to say that, while he was proud of her, she was not allowed to go off on her own, she almost smiled. I felt her ribs expand with a deep inhale and then release on a long sigh.

—

We first learned of Mada’s ability because she was never thirsty. In the summer months, she did not run to the water jugs the way other children did. I was always asking her to drink more water, and she was always reluctant. I did not think much of it, just a child’s picky demeanor, until the morning of her eighth birthday. Mada had gotten up early; I’d assumed it was to play with friends before school, but within an hour, she was back at my bedside, tugging gently on my hair.

Mama, here. For us. For my birthday.

I opened my eyes to the blurry outline of an object pressed too close to my face. What is it?

Drink!

A rim was pressed to my lips, and I realized I was being presented with a cactus leaf full of water. I sat up, causing Mada to jerk abruptly back. Where did you get this, Mada?

It’s not from the water stores, I promise.

I took the leaf from her hand, staring at the size of it. Surely we had harvested all plants like this months ago, when the dry season began. The drought had only been ongoing for a few years then, but already we were thinking of the future—wet seasons starved of rain, every last drop a gemstone. The first water expeditions were venturing into the hills.

Where did you find this?

She shrugged. The desert.

Is there more?

Her black eyes searched my face, confused by my sudden insistence. More cacti?

More cacti with water. Mada, are there more where you found this one?

Another shrug. Maybe. They’re good at hiding, so you have to be smart to find them. She gestured toward the leaf I held. That’s for you. Drink it.

I drank. Hope brightened the taste of the water, sweeping like a cool breeze up my spine, clearing all traces of sleep. Mada, we need to go speak to the Mayor.

Now?

Yes.

Mada spent the day wandering just beyond town, showing off every little corner that had once yielded water to her curiosity. We were amazed; she had had more luck within sight of the square than many adult-led expeditions far in the desert.

This is a true talent, the Mayor said.

She prodded the ground with a big toe, bashful.

Mada, do you think you can find water farther from town?

Maybe, she replied.

I laid a hand on Mada’s shoulder, shooting the Mayor a warning look. She is only seven years old.

Eight, Mada mumbled.

Eight. Right. It was her birthday, and in the excitement, I had forgotten. Eight, I said. Today is the anniversary of when she came to us.

Mada made a face up at me, and the Mayor crouched down to catch her eye. Happy birthday, Mada. Eight years old! That’s an important year.

Thank you, she said. A couple of seconds passed before she asked, Do you really want me to go out into the desert?

Mayor Annering and I considered each other over the top of Mada’s head. The girl was barely the height of my chest; she had only just learned how to build a fire. But there was no denying that we needed water.

No farther than a day’s travel, I finally said. And she needs to stay caught up in school.

The Mayor turned back to Mada and smiled. How would you like to go on adventures?

Mada said yes.

Later that night, after she had tired of spinning in the new skirt I gave her as a birthday present, she admitted she was afraid. There are wolves in the desert, right? And big snakes. And lizards.

The hunters will protect you. All you need to worry about is finding water. I motioned for her to change into her sleeping clothes. When she was done, I sat her in the center of her bed.

But what if there’s a scary animal? she whispered.

Then you can be like the desert fox, I whispered back. Small and swift. Run away, or hide. I threw her blankets over her. See? Such a good hider.

There was a burst of giggles as she wrestled her way back to open air. Mama, she said, with new solemnity. Do I have to go?

I sat down next to her. You will be helping the entire town. You have a talent.

She fiddled with the blankets around her. Okay.

Okay?

Yes. She flopped down onto her side and turned away from me. Goodnight, Mama.

Goodnight.

—

I suppose I have bored you by now with my tales of Mada not as a hero but as a girl growing up. But this is how I remember her, and I guess this is the only way I know how to talk about her. I miss her the way the land misses water, and the animal bones in the desert miss their flesh and blood.

Mada is not my daughter by birth. You might have already learned that from your parents. I did not carry her in my belly. I was far too old for childbirth when she was brought to me, a girl of no more than three years, kicking and crying all the way through my front door. She had been found by a hunting party asleep by the side of a well-worn trail. She was clothed, suggesting she had once been cared for, but she was so thin that her bent elbows could have been the points of two spears.

She spoke no words, and we decided she had likely been abandoned by a traveling family with too many children to feed. My first daughter, eighteen years, had just married into another town, and I was lonelier than the sun at the peak of the sky. They stood Mada before me, a tangle of knotted dark hair and dusty limbs, two tear-soaked black irises widened to the size of moons, and, suddenly, I could breathe again. Here was something to care for, someone to love.

—

I hope to still be alive when Mada returns. In my dreams, it is the Summer Festival. You and I and the whole town are gathered like we are today, around a bonfire; maybe we are even retelling her story, remembering. Mada wears the same orange skirt from when she was fifteen. She walks toward us, and behind her scurry foxes, tarantulas, lizards; overhead, owls and moths swoop; in the distance, low howls announce the wolves reacquainting themselves with the desert night. The air lets out a long sigh, relieved. I reach out a hand and in the center of my palm lands a drop of water.

Morgan Johnson • Apr 11, 2024 at 12:53 pm

I intended to say so after your reading, but this is so unbelievably wonderful. Your cadence of reading was compelling, one I’d like to develop eventually. Of course, going to your prose content, I fear I don’t have the language to articulate how much I love it. You place the reader in the setting with incredible speed and build something near mythic in a few short paragraphs (something I also want to master desperately). I’m obsessed with you!

Jessica Peng • Apr 29, 2024 at 7:38 pm

Morgan! I’m so sorry I didn’t see this until now, but you have literally made my day with your kind comment! I’m so so excited that you enjoyed the story, and I also absolutely adore your poetry—so subtle but emotional all at once. Cannot wait to read what you write next!