Asunción chopped the chicken into cubes because the dog does not like it any other way. Her knees hit the cold marble floor as she put down the bowl with chicken, broccoli, beef liver, sweet potato, and green peas.

“Don’t forget the joint supplements,” Mrs. Benson said as she stood from the kitchen table. Her black red-bottom heels clashed against the white of the house. A blue dress covered the least amount of skin necessary to function.

“I already put them in,” Asunción responded.

Mrs. Benson walked up to Jack, and without bending down to pet him, said goodbye in a baby voice.

“Asunción, I’m going out for lunch. There’s leftovers in the fridge if you want some.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Benson.”

The heavy mahogany door slammed shut. Asunción took out the leftovers from the fridge, the chicken and rice with creamy peanut sauce she had prepared yesterday. The food she cooked was part of her pay. So was her room. The Bensons used this to justify her low wage. Asunción was happy though. It meant all her earnings could go to her son in El Salvador.

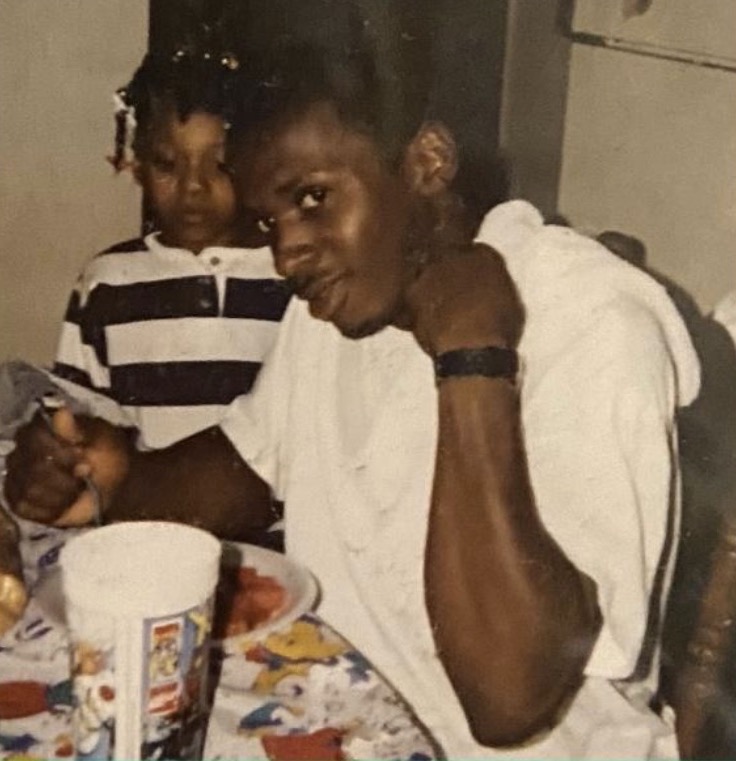

Asunción’s son was falling ill to malnutrition. She knew what it was like to be hungry, but it was nothing like the pain of knowing her son knew what it was like, too. She hoped in a few years, when he was old enough to work, he would move to the States with her. He was a fast learner. They say intelligence is inherited from the mother.

Asunción took a forkful of rice as Jack started barking.

“¿Qué quieres?” What do you want?

He was barking at a squirrel on the emerald-green lawn. Asunción placed her hands on her chest and groaned in discomfort as she got up to open the sliding glass door. Jack zoomed past her to the place only he used. It was his backyard.

She took a deep breath, and on the way back to the kitchen, she stopped to look at the now-empty dog bowl.

Puto perro.

***

Asunción could not go to sleep until the Bensons got home. She was responsible for making dinner and cleaning up after them. All so the kitchen would be spotless for when she dirtied it again for breakfast.

She prepared Jack’s food again. For dinner, he was eating minced meat, egg, yogurt, apple, and ground bones. She looked at the supplements on the kitchen counter, and after some hesitation, put the appropriate amount in the bowl.

Food in hand, she slowly walked over to the corner where Jack waited. He sat there, sweeping the floor with his tail. Asunción stood over him as if expecting something out of Jack. A thank you, perhaps. A sign of gratitude. Appreciation.

She fed him.

The Bensons got back from supper. A few hours before, they had texted Asunción to not cook anything for the night. She would go to sleep hungry.

“Can you lock Jack in his cage when he’s done eating?” Mr. Benson asked. “I’m going to bed.”

“Yes, sir. Good night.”

Mr. Benson walked away. His body dwindled down the museum-like hall.

While Asunción waited for Jack to finish eating, she thought of the remittance she had sent home four days ago. The stress of not knowing if the money had been received by her mother kept her up at night. With no one to help or teach her, she entrusted the Bensons with transferring the money. She once overheard them saying it was a waste—that the money should be reinvested into the local community, but that’s what she thought she was doing.

Once the dog bowl was empty, Asunción locked Jack in his cage. His groomed and soft coat hit the memory-foam bed.

Asunción walked to her room on the opposite side of the house, near the garage. She laid on her twin bed, covering herself with a once-white, oatmeal-colored comforter that smelled of dust. She grabbed her rosary, ripping the nightstand of its only possession.

“Dios te salve, María, llena eres de gracia; el Señor es contigo…” she started, fighting sleep until it won on the twenty-seventh bead.

***

Asunción woke up to the feeling of someone watching her. She squinted to try to make out the figure in front of her.

“¿Imanuel? ¿Hijo?” she asked, expecting to see her son.

She looked closer, only to find Jack by the closed door. He had a smile on his black muzzle, panting as if he had just come from outside.

“¿No me dejas sola, no?” She wanted to be left alone.

Asunción stared at Jack’s shiny fur and plump face. She noticed his muscular hind legs and robust belly. She couldn’t help but think of her son. Her jaw clenched, and her eyes watered.

She clasped her hands, and in a different type of prayer, an invocation from human emotion, she wished ill on the dog. On Jack. The innocent German Shepherd whose tongue hung out for her.

The figure began to dissipate as sleep engrossed her.

***

Asunción woke up to the blaring screams of Mrs. Benson.

“John!” The name tunneled through the house.

Asunción heard the beat of stone and rubber made by Mr. Benson’s slippers as he ran. She tried to get up, but her lungs felt like anchors. She clenched her teeth as hard as possible as she limped to the living room, panting and leaving hand-stains of sweat on the walls.

On the floor, Mrs. Benson and Jack sat like a pietà. His breathing filled the room. His limbs hung from her body.

“What happened?” asked Mr. Benson with marble eyes.

“I went to get water and heard Jack gasping, so I looked over at his cage and found him dying in it.”

They turned to Asunción, who was now clutching the hallway’s corner.

“What did you feed him yesterday?” Mrs. Benson asked as she continued to caress Jack’s head.

“I fed him what I always feed him on Wednesdays,” she said. It was true, but she couldn’t bring herself to look at the dog.

John rushed to Mrs. Benson and picked Jack up, carrying him in his arms. “We have to rush him to the vet,” he said, dashing to the door.

“Asunción, stay here. We will be back,” Mrs. Benson said as she exited the house. She pushed the door, but it did not close. The car’s motor turned on.

Asunción tried walking to the door. Her shoulders dropped like anvils. Her lungs shrunk with each breath. She attempted to lean on a console table but fell face first. Blood dripped down her forehead onto the floor. At least it was smooth, easy to clean.

She mustered the energy to reach for her phone in her pocket and call the Bensons.

“Hello?” Mr. Benson said. The sound of passing cars busied the background.

“… I,” she took a deep breath. “I think I’m dying.”

“What do you mean? You looked fine before we left.”

“I need help,” she responded. A red halo continued to form around her head.

“There’s some Tylenol in the cabinet next to those herb things you take. That should help,” Mr. Benson said.

“At least more than whatever she’s been taking,” murmured Mrs. Benson, loud enough for the microphone to pick up.

“We just got to the vet, so we will have to call you later.” After five seconds of silence, Mr. Benson hung up.

Asunción considered calling 911, but she remembered the stories other migrants told her on the way to the United States. “Don’t get sick. They will deport you if you go to the hospital. It happened to my prima Maribel,” one of them said. “It also happened to my brother,” said another. She also had no means of paying. She was uninsured. She hoped prayer would give her the best chances of survival, but after several Our Fathers and Hail Marys, she cried. Water mixed with blood. She knew this was it for her, so she asked for forgiveness for all the wrong she had done. The water bottle she stole when she was seven. The lust she felt for her neighbor Manuel. The envy that led her to wish death upon a dog.

With no money to go to a hospital and no time to go home, she closed her eyes and went to where all life meets.

***

The laughter of a child and his grandmother woke Asunción up. She was now surrounded by the potholed streets and tin-roofed homes of San Salvador.

She walked toward the voices, and when she was close enough, watched and listened.

“Te tengo una sorpresa en la cocina,” announced the grandmother.

Imanuel beamed at the news of a surprise. He closed his eyes and let his grandma guide him to the kitchen. It smelled like chicken. Like real chicken. Not broth.

“Tu mamá nos mandó comida otra vez,” she said smiling. Your mom sent us food again.

The counter was jeweled with chicken, ground beef, carrots, peas, eggs, sweet potatoes, rice, beans, and plantains. The grandma took the pans off the gas stove and served two plates of chicken and rice with peanut sauce.

“¡Mi favorito!” Imanuel said.

They sat down on a plastic table and offered thanks before eating. Imanuel looked up at the sky, and the sky looked back.