The children all have their faces smudged against the school bus windows, pushing and shoving to get a better view of the figures moving behind the barbed wire fence. They are in fourth grade and on the way to the aquarium. All of them have driven down this stretch of road before—it’s the only way to get to the city from their town on the fringes of suburbia—but none have ever seen activity outside the building before. The chaperones, now standing with their arms braced between the two cracked maroon benches at the front of the bus, are trying and failing to bring the cacophony back to order.

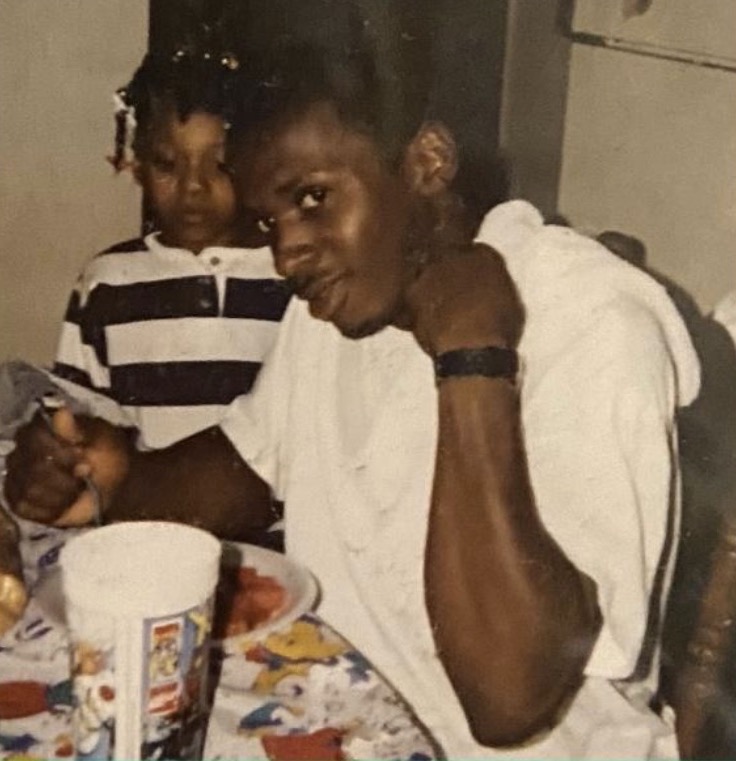

“I wonder what they did,” the girl comments to no one in particular. The prisoners are wearing all-white and are unidentifiable at this distance and through the harsh sun. They move like dolls in a straight line along the fence a few hundred feet from the highway. Black, lumpy trash bags seem to grow out of their legs and backs as they carry their possessions across the complex.

The boy from across the aisle has rushed over and is crowding her to get a better view.

“I bet they’re murderers.” He gives her a gap-toothed grin. The girl, Annabelle, doesn’t respond, but both their heads twist to keep the grey concrete form of the prison in view as long as possible.

Annabelle knows that prisons are bad. Not in the excited way of her classmates, where the promise of wrongdoing is almost salacious, but in the pragmatic language of concrete and fences. The walls are weathered and have sooty grey streaks running down them like tears. The only thing she knows about her grandfather, her mother’s father, is that he built prisons. She doesn’t know if that makes him good or bad. She also doesn’t know if he built the prison they just passed on the interstate. Maybe he did. The only time her mother has brought it up was when they were passing that same brutalist concrete building over a year ago going in the opposite direction.

They were leaving Nice House and moving into Little House. Vic had been tapping the steering wheel with her index and middle finger with a staccato rhythm the whole drive, in a way that Annabelle would now label as needing a cigarette. But her mother wasn’t smoking a year ago in what had become another short-lived effort to quit. A final holdover from David.

“They say he was the best concrete pourer in the state.” Vic motioned to the behemoth they were passing.

“What’s he like?” Annabelle looked at her mother’s face in the rearview mirror. Are all mothers so beautiful and sad?

Vic was lost in thought about what it means to be the leaver versus the left. Her father went and built another family when she was twelve. He did it like it was an easy thing to find a new wife and have another batch of kids. She hated him for it. She hated him more because he had three kids with his second wife and didn’t leave them. And here she was, driving away from David.

Vic realized that Annabelle was still waiting for an answer about her grandfather. “The dust on his hands would always clog the sink.”

Annabelle also knows that sinks are important. The sinks in Nice House were glistening white porcelain with shiny silver drains. They were deep and square, set into stone countertops and with foaming soap next to them. Sometimes Annabelle would pump a heap into her hand to smell the lavender scent better. The sinks in Little House had stubborn yellow lines stained into them. She used to be scared of how the drains gurgled loudly if she left the water running too long while brushing her teeth. But she likes how they’re round and scalloped like seashells and how the contrast of smooth teal tile and rough grout feels beneath the pad of her finger as she traces the countertops.

***

Vic was twelve and standing at the threshold between the kitchen and her bedroom. The house was full of hastily pasted-on additions and she could see the glowing green clock of the oven from her bed if she left her door open at night. It was close to dinner time and her father was standing at the kitchen sink washing up after getting home from work. The smell of sweat, cigarettes, and concrete mix mingled with the roast chicken her mother had in the oven. Her mother, Mallory, was mashing potatoes on the stovetop but stopped and turned to face Buford’s back.

“Hillary’s bridal shower is this Saturday.”

The kitchen was flooded with the sound of running water hitting the metal basin of the sink as Buford remained silent.

“It’s in Crane. So, I’ll need the car.” Mallory was still holding the masher and Vic anxiously watched a lump of potato slide down the prongs towards the floor.

Buford kept his hands in the stream of water.

“Mitch’s card game is on Saturday.” The water became a cloudy gray as it passed through his fingers.

“You play cards with Mitch every week. It’s my sister’s bridal shower, for God’s sake.”

Buford picked a soggy lump of clay out from under his fingernail.

“Well?” Mallory’s grip was white on the masher but her voice did not betray the strain.

He turned the tap off.

“I’m not going to have you crash my car for a stupid party.” He dried his hands off and finally turned to face his wife.

Mallory stood with her lips parted in mute disbelief.

“But Daddy!” Vic interjected. Her parents turned to face her. Her mother made a small shaking movement with her head.

Something like betrayal flared in her father’s eyes. “Stay out of it, Victoria.”

Her father left the room and her mother returned to the interrupted task of mashing potatoes. Vic walked to the sink and saw a pool of cloudy water bubbling slowly down the clogged drain.

David’s new girlfriend is dropping Annabelle off from visitation and Vic is smiling tightly from the doorway of Little House. Little House is small and yellow, with a crumbling cement front porch. The spring-loaded screen door is pressing into Vic’s shoulder. Beyond this tense opening is the crowded and homey interior of Little House. There is a sweetly-shaped loveseat in the living room with a garish Minecraft blanket thrown over the back. Annabelle’s room is painted green, her favorite color, and the ceiling is crowded with glow-in-the-dark stars.

The new girlfriend is young and pretty. Vic raises a hand in greeting and goodbye as her daughter climbs the steps with her weekend duffle bag flopping against her legs. Vic takes the bag and kisses the top of Annabelle’s head, her arm wrapped protectively around the girl’s scrawny shoulders.

“How was your weekend, Belly Bear?” Vic tries to distract herself from the beating in her chest by studying the small dimple on Annabelle’s chin.

Annabelle rattles on happily about her weekend. David gets her two weekends a month and that’s about all Vic can bear. Annabelle takes a breath, “and then we went with Natalie to get ice cream and we fed the ducks at the lake.” Vic guides her into the house. “And Natalie says that bread is bad for ducks so we fed them frozen peas.”

“I’m sure they loved it,” Vic says absent-mindedly, still thinking about the girlfriend. David should have driven Annabelle. It’s an hour’s drive on a Sunday, for God’s sake. Vic’s cell phone is ringing on the kitchen table. She walks over and sighs when she sees the caller ID.

“It’s just one fucking thing after another,” she murmurs under her breath. “I have to take this Belly, how about you unpack and grab a snack?” Vic is already opening the back door to the sad little patio. She only smokes outside.

Vic recognizes the irony of it. That a cancer radiation technician smokes the little devils. Annabelle’s school had a presentation in gym class a few months ago about the dangers of smoking and she came home crying about how she didn’t want her mom to die. Vic knows enough about death to pretend to smoke less around the girl, but she’s also seen enough decaying bodies to know that she’s going to die regardless of the cigarettes. David never understood it either. That was one of the last fights they had.

He expected Vic to be grateful. They were standing in his pristine kitchen, after all.

“I don’t know why you’re so committed to being white trash.” He held up the pack of Marlboros with an accusatory flourish. Vic had been hiding that she had taken the habit up again. She was an expert at on-again-off-again relationships.

It was like all love songs that weren’t quite love songs. David had met Vic before she was anything. Just young and broke and alone. Now she was less young, less broke, and still lonely.

“It feels like I’m living in a fucking prison.” Vic snatched the half-filled box from his hands. David sighed indulgently.

“Victoria…” He said it like it was obvious he had the upper hand.

Annabelle hadn’t been a planned pregnancy. Vic was still dragging herself through undergrad. But contemplating the positive test in her grimy dorm bathroom made it seem like a good idea. David was rich. Nice enough. She had thought being a mother would help her escape the angry, petulant parts of herself. Instead, she learned that growing up didn’t happen symmetrically.

The phone is still ringing. “Hi, Andie.” It’s her half-sister.

“The doctors are saying Dad’s gonna die soon. Something about holes in his lungs.” Andie pauses awkwardly. They aren’t close. “I just thought you should know.”

Vic is holding a smoldering cigarette between her fingers. She takes a drag.

“Thanks for calling. I guess he should meet his granddaughter before, ya know.”

“Yeah, I s’pose so.” The two women stay silent on the call for a few seconds, maybe contemplating how the other represents the faults of the dying man. The hurt of being the abandoned daughter and the fear of being a repeat. Neither knows who hangs up first.

***

It’s raining and Annabelle is watching water droplets chase each other across the car window. They’ve already been driving for three hours and she is holding her questions in her mouth like a bubble.

Are we there yet? Is this where you grew up? How long has it been since you’ve seen him? Are we there yet?

Annabelle knows about grandparents. David’s parents visit sometimes. They are stiff and proper people. At dinner they talk about money with David and, back when they all lived in Nice House together, they made small little comments about how her mother should be mothering differently. But these facts were not all that important to Annabelle. The three of them play spades together and if she is losing her grandmother leans over and taps the card she should play with a beautifully manicured nail. They say when she’s a little bit older she can learn to play bridge with them, or poker. Maybe even mahjong, which the grandmother plays every week with her friends in the country club game room. Annabelle likes how they made her feel so grown up.

She doesn’t know what to expect from this man who built prisons, though. In her mind, he was more cement than flesh, dusty chunks of him disintegrating and drifting through the house. Annabelle had never met someone who was dying before and her mouth felt dry from the thought of ashes.

The same unasked questions were also on Vic’s mind. The last time she had spoken to her father it was about the foundation of Little House. She was deciding whether the cracks were worrisome.

Vic took a deep breath before dialing. “Hi, Dad.”

The old man coughed phlegmily into the phone. “Whataya want?” His lungs were already bad a year ago.

“I’m looking into a house to rent and am worried about it having a cracked foundation.”

“To rent?” He coughed again. “Fuck does it matter to you then?”

“I dunno. I don’t want it to leak or be dangerous or anything.” Vic hated feeling stupid, which the old man had a talent for inducing.

“Nah. It’s a piece of shit, but plenty of buildings are pieces of shit nowadays.”

“Oh. Okay.” She already regretted calling him.

There was silence. “Rent? That mean Whatshisface is gone?” Of course he didn’t remember David’s name. They’d only been together for ten years.

“Yeah.” She sighed. It felt like the breakup was all she talked about these days. “I left him.”

“Never liked him.” She could hear the old man spit. “Never married you, did he?”

Vic almost felt like smiling. It was nice to hear something other than pity about the whole ordeal. She supposed he didn’t have much of a leg to stand on when it came to judging someone for leaving.

“No. We were never married.” It used to bother her, but now she was thankful she didn’t have to deal with all the paperwork of divorce.

“Hmmph.” A pause. “And you got that girl? How old is she now?”

“She’s turning eleven next month. She’s a good girl, real smart.”

“That’s good, Victoria, that’s good.” Vic could hear some sort of commotion on the other end of the line. “Well, dinner’s ready so…” Her father trailed off, always a coward when it came to ending conversations.

“Take care, Dad.” Click.

They hadn’t spoken since then. Vic had texted him a few days ago letting him know they were coming and had received a meager “OK.” in response. She hadn’t been in the same room as him since college, probably, and didn’t know what to expect. Sure, she had seen a lot of cancer patients in the clinic, but she had never known them when they were well.

They pass through the storm and emerge in a dusty brown town.

“We’re close,” Vic says, relieving Annabelle of her most burning question.

“Is this where you’re from?”

“Not quite. My mother and I lived in a different town a few miles down the interstate. Your grandfather moved here after he got remarried.” Vic doesn’t mention how the actual timeline wasn’t so tidy.

They pull off the road onto a patch of dirt in front of a trailer. It’s brown too, and there is a brown dog lying on its side by the cinder block foundation. The dog lifts its head and thumps its tail lazily in the dirt.

“I guess we’re here.” Vic is nervous and steps out of the car slowly.

Annabelle slips her hand into her mother’s. Vic gives it a squeeze. The weathered wood of the front steps creaks beneath their feet and the door makes a hollow sound when Vic knocks on it.

His wife opens the door. “Hello hello. How was the drive?” She steps aside to let them into the narrow living space.

“Hit some rain outside Fort Stockton. Nothing too bad though.” The first things Vic notices are the persistent beeping of an oxygen machine and the smell of antiseptic.

Vic’s father is sitting in his worn-down recliner, his chest moving quickly and shallowly. The clear plastic tubing of the cannula splits his face in half. His brown eyes are watery and the whites are slightly yellowed. His leathery skin is draped loosely around his bones. It is easy to make the same conclusion as the doctor.

Annabelle is intimidated by the machine and the harsh set of the man’s mouth. He reaches out a hand to the girl. She steps forward and shakes it. His cracked and calloused fingers wrap around her young and soft ones.

“Hi, Grandpa,” Annabelle says shyly. The man is still holding onto her hand as he studies her face intently. Up close, the earthy smell of an animal waiting to die battles against the harsh brightness of disinfectant.

“Pleasure to meet ya.” He gives Annabelle a smile with his tobacco-stained teeth. She takes this opportunity to slither her hand out of his.

“What’s the dog’s name?” Annabelle backs up into her mother, who gently strokes her head.

“That’s Lady. You like dogs?”

Annabelle nods vigorously.

“Well, I’m sure Lady would love for some little girl to pet her.”

Annabelle looks up to Vic for permission. She had been petitioning for a pet for months and the idea of petting a dog was infinitely more appealing than looking at the dying stranger. Vic nods. “Just stay close to the house,” she cautions.

Vic sits across from her father in the unfamiliar interior of the single-wide. His wife is keeping herself busy and unavailable in the kitchen.

“How long have you lived here?”

He smacks his tongue dryly against the roof of his mouth. “Few years now. Other place got too expensive once I retired.”

“Mmm.”

The wife clatters some pans in the kitchen.

“Staying for dinner?” he asks.

“If you want us to.”

“Sure. Why not.” He adjusts the placement of his cannula over his ears.

Vic doesn’t know what she was expecting from this pilgrimage. Maybe for the man to have gotten better, like how a dying star shines brighter before it’s doomed. Instead, he’s still him, and she’s a little girl all over again: desperately wanting to be near him when he was away and still lost when he’s around.

“You smoke?” He pulls out a pack from his chest pocket.

Vic rubs her tongue against the smooth interiors of her teeth, thinking. “Yeah.”

She helps her father stand from the chair and drag his beeping machine and tubes to the narrow front porch. They sit side by side and Vic is worried about getting splinters in her jeans. She takes the cigarette he offers and watches as he unsuccessfully tries to strike his lighter. His hands are too weak to perform the familiar action. He doesn’t look her in the eyes as he passes it to her.

They sit in silence for a while, holding their vices in their hands and watching the girl try to convince the dull dog to sit.

Vic can hear the pressurized air whoosh in and out of her father’s leaky lungs.

“Maybe you should quit,” he says.

Vic watches the ash flutter off the butt of her cigarette and feels that smallest spark of warmth between her fingers.