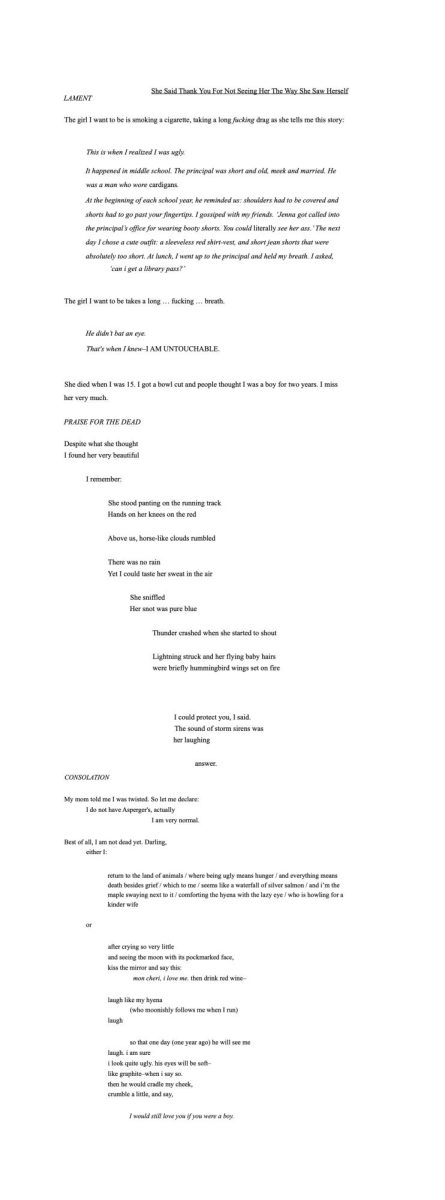

我们的鬼图书馆

(Wo Men De Gui Tu Shu Guan)

or

Our Ghost Library

This is the most beautiful place he’s ever had the misfortune to stumble upon, and even as he exhales in wonder, Piggy curses the revolution. Fuck them. Fuck the Red Guards. Fuck Chairman Mao—He is the reddest, reddest sun!—and his ancestors to the

eighteenth generation.

Because Piggy has to burn it all to the ground.

It’s the bloody, blood-Red August of 1966, and their summer homework is to seek out and destroy the Four Olds (Old Ideas, Old Culture, Old Customs, Old Habits) to usher in the Four News and herald China’s new age of proletariat prosperity. Not that they actually do any homework anymore. Piggy remembers these lessons all too well, pounded into his soul by golden hammer and sickle with more violent zeal than any his classmates had ever demonstrated for math or science or literature. Or history.

Piggy loves history. He grew up listening to Mama’s bedtime stories of cunning and courageous warrior generals, emperors just and tyrannical, scholar-officials centuries ahead of their time—the way these men and women who had once taken the fate of the world in their own hands and built it up, brick by brick, now merely ghosts whose names danced upon the silver tongue of a middle-aged housewife in Beijing, were immortal as long as you remembered them. He grew up watching Baba pore over text-dense tomes and documents, face wan and weary yet eyes alight over his research. Baba had been a professor at Peking University, the renowned head of the history department, before they’d stormed the institution and set fire to his life’s work. Piggy had been there. Piggy is a Red Guard. Piggy’s parents are traitors and class enemies, and Piggy is loyal to Chairman Mao just like the rest of his peers.

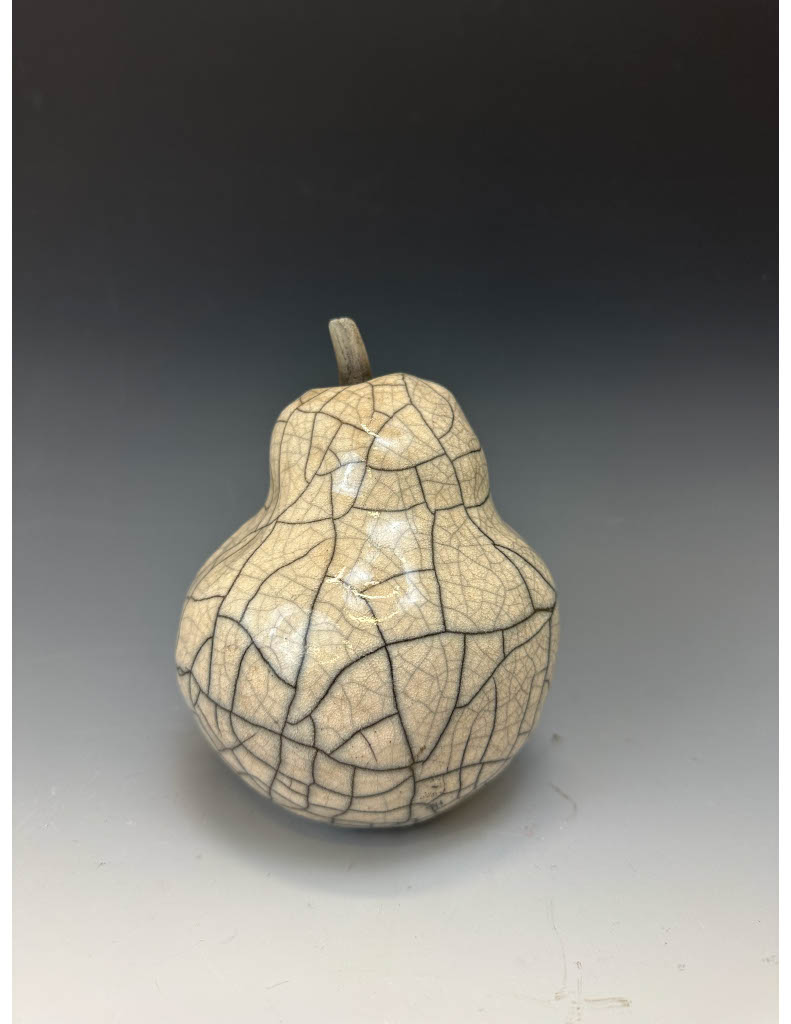

It takes Piggy a while to realize that this place is a library. But it’s not like any he’s ever seen before, even within the polished white marble halls of Peking University. Piggy’s standing in the middle of a spacious siheyuan, a traditional quadrangle courtyard, and his footsteps echo across the smooth stone tiles as he crosses the courtyard towards the main building. The building has red walls and a traditional sloped roof. The architecture is elegant but not ostentatious. Despite all the anti-old reeducation Piggy’s undergone, he can’t help but recognize and appreciate the symmetry, the traditional feng shui elements. The air is frigid yet permeated with the faintest scent of smoke and charred wood. It’s heavy with somber silence yet not stale, not quite like a tomb but rather like a temple or church. Such holy places are banned in China, of course—the only god they’re allowed to worship is the specter of communism and its holy prophet, shining sun and savior Chairman Mao.

Piggy’s breath catches when he steps inside and finds himself engulfed by a fortress of shelves. Shelves upon shelves tower overhead, each bearing a treasure trove of books and scrolls. All of them look ancient. Piggy glides through crammed aisles, skimming titles and running his fingers along gossamer-thin pages and wooden strips, drinking in the dense inked sprawl of ancient Chinese calligraphy. It’s called seal script, he recalls Baba telling him, from the Qin Dynasty. From 200 BCE, roughly two millennia ago. He is not supposed to know this anymore. He is supposed to destroy this.

He can’t destroy this.

Piggy has to destroy this. His very first lesson in “How to Be a Perfect Little Communist (Or Have the Living Shit Beaten Out of You)” will always have a special place in his heart. It was a gang of Mao-suited young men, as they always like to think of themselves, though they were barely out of junior high themselves. They’d been learning about book burning by Emperor Shi Huangdi during the Qin Dynasty. Mr. Wen had always had a way with words, teaching his students without seeming to actually lecture them. And then the men—mere boys—had barged in. Shoved Mr. Wen aside. Erased the dates and names from the chalkboard, grabbed the children with bruising grips and forced them to write: Destroy the Four Olds. Defend Chairman Mao with our blood and life. To rebel is justified. Then they’d lined the children up like pigs, herded them out to the school courtyard, and made them burn all their textbooks.

Piggy doesn’t like to think about it. He doesn’t like to remember how expensive those books had been, how hard Mama and Baba had worked to earn them for him. He doesn’t like to remember Mr. Wen scrambling after the children, protesting, and then being shoved to the ground a second time—harder, and not getting back up again. Books being burnt, school desks and chairs being flung, chalkboards being smashed. Mr. Wen, still and prone, forehead glistening red. They must rebel or face the same fate.

He has to do this.

Piggy reaches into his pocket, pulls out his lighter. He glances around him. Everything is highly flammable. How do you even begin to destroy a library? Should he knock everything off the shelves, topple the bookcases? Should he tear up the books, rip apart the scrolls? Should he set fire to the nearest shelf? He is a loyal model student comrade, and nobody can accuse him of sympathizing with the old China. He hesitates. He wonders if he actually has the heart.

And then someone grabs his arm from behind.

“Don’t you dare.”

Piggy whirls around.

It’s a young man, barely older than Piggy—the strangest boy he’s ever seen. He looks like he’s from the ancient past. He’s dressed in hanfu, traditional Chinese clothing: long, loose-fitting, pitch-dark shenyi robes. His hair is neatly tucked away beneath a simple black futou cap. His starch-white collar has overlapping lapels that cross left over right. His eyes are burning into Piggy with the mythological force of ten suns.

Piggy reels. The boy smells like smoke and ash—sounds like it, too. His visage, proud and aristocratic, shudders before Piggy’s eyes, as if he’s not flesh and blood but a mere mirage. His fingers dig into Piggy’s skin, searingly cold, yet his grip feels brittle to the touch. Soft, almost desperate.

Inexplicably, Piggy thinks to himself that the boy’s been burnt once and will not be burnt again.

“Who are you?” Piggy asks. He wrenches his hand free from the other boy’s grip, stumbles back, shoves the match back into his pocket.

But before the boy has a chance to answer, Piggy’s eyes snap back to his collar. He realizes. Zuoren. Left over right. Hanfu collars are always supposed to cross right over left. The other way around is only for the dead.

Piggy panics and flees.

His name isn’t actually Piggy, of course. But he’d supposedly been quite the hellion as a child—stubborn, his mother says, obstinate, and, well, pigheaded. She’s never meant it as an insult. Chinese parents always nickname their children after undesirable traits—silly, awkward, mischievous—out of both affection and superstition, in the hopes that monsters will be deterred from stealing them away. Maybe Piggy’s parents had also hoped that he would grow up to be the opposite of his nickname someday.

Now Piggy is a communist and his father is in jail because Piggy had reported him for harboring counterrevolutionary sympathies. The last time he’d seen Baba had been after the Red Guards had ransacked all the major universities and academic institutions in the city. Men and women, charged class traitors, had knelt surrounded by their accusing coworkers and friends and family—even their own children. By the end of the struggle session, Baba’s glasses were shattered, his teeth kicked in, and his ribs broken. Piggy doesn’t know what expression he’d worn because he hadn’t been able to look back into his father’s eyes. And no one knows where his mother is, or whether she’s alive or dead.

Piggy continues to go through the motions. Seize classrooms, storm institutions. Praise Chairman Mao—Chairman Mao is the Great Red Sun in the Hearts of the People, he reads and hears and chants again and again and again. Terrorize schoolchildren and attack schoolteachers, destroy school bags and school desks and school books. Chant, scream, plaster up red posters and put on red armbands and swear by the “Little Red Book”—Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong. Destroy banks and private homes, destroy museums and tombs, destroy temples and shrines and churches and cathedrals and mosques. Chant, scream, shut up, don’t say anything. Destroy libraries and all the knowledge they hold. Chairman Mao—always fucking Mao, Mao, Mao. Destroy, destroy, destroy. The fucking Great Red Sun.

It’s not long before Piggy caves and returns to the library. That library. The boy he met, Piggy thinks during scarce, stolen moments of self-searching, must be a ghost—must be the guardian of the library. Hence, Piggy calls it “Ghost Library” in his dreams; indeed, he dreams of it every night now. He doesn’t dare to name it in his waking thoughts. The people say Chairman Mao is a sun, a god. They whisper of thought reform, whisper suspicions about and against each other, and Piggy thinks they must be able to read minds. Does the state own all its people’s thoughts? Can he still call his mind his own? Piggy buries the Ghost Library deep within his heart so it can’t be washed from his brain, too.

The Ghost Library is even more beautiful than he remembers. The air seems clearer, cleaner. Wary, yet not unwelcoming—cautiously hopeful. The sky is a blinding static white, overcast yet still brilliant, and the hewn stone edges of the building smear into blurred lines. The red walls are paler—far from the strident Maoist red he’s used to—and the jade-green window lattices are brighter. The glazed tiles of the ridged roof collect cloud-filtered sunlight off their upturned edges like light-shot beads of rain. It still smells faintly of smoke and ash, but this time around, Piggy can pick up other notes, too—the earthy vanilla aroma of old books. Of course. He’s surrounded by them. How did he not pick that up last time? He goes through the aisles and chooses scrolls at random, gently unfurling the sewn bamboo strips, brushing his fingers against the calligraphy in quiet awe. He wonders what it’d be like to be able to read them.

“It’s happening again, isn’t it?” the boy says from beside him.

Piggy looks up from the scroll he’s holding. The boy gazes back at him gravely. He has dark hair and beady half-moon eyes, a low-bridged nose, yellow-brown skin. At second glance, he doesn’t actually look so strange; his physical appearance is like that of any other young Chinese man. If it weren’t for his time-displaced Qin Dynasty robes, he could even be one of Piggy’s classmates. It’s the way he carries himself that makes it seem like he belongs to a different species. Piggy savors the strangeness of the thought that people thousands of years apart can still look the same.

“What is?”

Still holding Piggy’s gaze, the boy leans against a bookcase. His appearance is loaded with oxymorons—demeanor reserved yet self-assured, face affectedly bland, shoulders tense and burdened with cerebral poise. He gives a guarded shrug, and Piggy is startled by the gesture’s casualness, by the fact that it’s so universally human. “Book burning.” The boy’s voice is a dry whisper. “You’re destroying them again. Books, knowledge…wisdom. You kill anyone who thinks differently, who thinks at all.”

Piggy swallows hard. “What’s it like? Dying, I mean?”

“I’m afraid I’ve been robbed of that right for the time being.” The boy looks away, into nothingness. His voice reminds Piggy of the wispy tendrils of smoke that always linger after burnt paper has long curled and crumbled away into pungent black scraps. “I was buried alive, as were all the other ru scholars. It was on His Imperial Majesty’s orders, you know.” He pauses and frowns. “But perhaps you do not, seeing as they’ve begun burning books again. How could you learn, then?”

“I do know.” Fenshu kengru. The burning of texts in 213 BCE and the execution of over 460 ru scholars, the nation’s best and brightest, the following year. All for the means of further strengthening and spreading legalism. Piggy loves history, still.

Piggy is viscerally aware of the fact that his pockets are empty this time—no lighter. No burning.

“I cannot die,” the boy says. “Not yet. Not until I can rest knowing my library will be in safe hands.”

“How will you know,” Piggy asks, “when it’s safe?”

The boy finally looks back at Piggy. His gaze is pointed, penetrating. Assessing. “Someday,” he says evenly, “there will come someone I can trust, to care for this library after my time. A new Guardian.”

Piggy hesitates. It’s just beginning to dawn on him, how fiercely the boy treasures this library. “Last time I was here, I almost burned everything to the ground.” He’s glad he didn’t. “Why aren’t you chasing me away right now?”

The boy gives a long, drawn-out sigh. Weary, yet resolute. “I believe that knowledge should never be hoarded or hidden away. It’s not a gift—it’s a right, that everyone should have. Do you still intend to destroy this place?”

“I do not.” Piggy knows it’s the truth as soon as he says it.

“Then you are welcome here,” says the boy, the guardian of the Ghost Library, simply.

Piggy takes these words to heart. He returns to the Ghost Library sporadically yet often, never failing to contribute something of his own upon each visit. Instead of lighters, he now brings a wealth of knowledge: books he’s managed to steal away from burning libraries and schools, historical records smuggled from the still-smoking ruins of museums, political documents and essays from toppled government buildings, Western literature, scientific research papers, articles on modern, innovative commercial products. Anything he can get his hands on, anything he can save from his fellow communists. The guardian of the Ghost Library welcomes all.

The boy tells Piggy everything he knows about the rise of Shi Huangdi, the first ever emperor of China. In return, Piggy tells the boy about everything that’s happened since. Obsessed with immortality, Shi Huangdi had died at the ripe old of age 49 in his quest for an elixir of everlasting life, and his—decidedly mortal and rather ironically short-lived—family fell from power soon after. Piggy tells the boy how the Qin Dynasty ended in 206 BCE and the Han Dynasty began in 202 BCE, then the Jin Dynasty several centuries later, then the Sui Dynasty, then Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing, then the Republic of China, then finally whatever the fuck has been going on since the communists won the Chinese Civil War back in 1949.

Piggy tells the boy about Buddhism, which was first introduced to China during the Han Dynasty. He tells the boy about the only female emperor in Chinese history, ice-cold badass and literal baby-killer Wu Zetian of the Tang Dynasty. He tells him about how, after the fall of the Qing Dynasty, men were executed if they refused to chop off their traditional queues (“Liu fa bu liu tou, liu tou bu liu fa.” Cut the hair and keep the head, or keep the hair and cut the head), even though up until then they would have been executed for doing just that. He tells him about how the Qianglong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty is widely, and rightfully in Piggy’s most respectful opinion, regarded as the worst poet in all of Chinese history. He tells him about the Great Wall of China, which has been around since the Zhou period, since before China was unified during the Qin Dynasty, and has since grown exponentially through the combined efforts of all the succeeding dynasties, especially the Ming Dynasty.

Piggy tells the boy that the Great Wall can be seen from outer space—oh, by the way, the Russians landed on the moon seven years ago—and then he realizes how out-of-the-blue that must sound and proceeds to tell him about rockets, satellites, radios, computers, electricity, and nuclear energy. Oh, by the way, the Americans have atomic bombs and they destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Oh, by the way, the Japanese destroyed Nanjing. Yes, yes, we’re probably decades behind all the other countries for the time being—Cultural Revolution and all that—but, I swear, you’d be amazed by the science and technology in the world right now. Just give it a couple more years, I promise.

For the next two years, Piggy destroys libraries and burns books along with several million other boys and girls all across the nation. He storms schools, seizes government buildings, razes museums, wrecks places of worship. He chants and threatens and accuses, beats and even kills. He never sees either of his parents again. (Mama is never found. Baba is either killed or made to kill himself. You’d be surprised at how many ghosts there are from these two years alone.) But unlike his parents, Piggy never slips up. He never becomes a class traitor. He never gives them any reason to turn against him. Unlike so many others, Piggy survives.

No matter what, Piggy does not give away the existence of the Ghost Library. It’s a secret, his very own, and not even the state can take that away from him—communism and collective ownership be damned.

In December of 1968, Mao Zedong decides he’s finally had enough of the Red Guards—as it turns out, having millions of teenagers constantly committing acts of extreme violence in your name can get old real fast—and launches the Down to the Countryside Movement. Sixteen to eighteen million youths are rooted from their urban lives and thrown into rough, rural areas to do backbreaking labor. Everyone says this is so they can be reeducated, so the educated youth can better integrate themselves into the working class. But everyone knows this is because they are tools that have outlived their usefulness.

Right before Piggy is shipped off from Beijing, the capital of China, to some nameless backwater village, he returns to the Ghost Library and finally musters up the courage to make the promise that’s been sitting on his tongue for almost two years now, waiting to take flight on wings of hope. He is weary and jaded, used. He has blood on his hands, ghosts on his conscience. He’s become a monster.

Grim prospects lie ahead, and Piggy deserves them. But he is not afraid.

“I don’t know when next I’ll be able to return,” Piggy begins.

The boy peers back at him, a probing look in his eyes. “When, not if. So you will return, then?”

“I swear it.” On my life, on my honor, on my eternal soul. On spilt blood and on felled bodies. On eons past, on the faith I still dare to have in the future. “I swear I will return.”

I swear it on all the places I’ve destroyed, on all the people I’ve killed. On Mama and Baba. On forgiveness.

“And then?” The boy sighs, and then he says Piggy’s name—not his nickname, but his real, full name. The one he was born with, the one his parents gave to him what seems like ages and ages ago. Piggy’s almost forgotten it, himself. “What comes then? What will you do after?”

Piggy pauses. The boy’s scholarly robes and cap are still neat and smart and ink-black, as always—yet something about him seems inexplicably paler. Like he’s fading away. He barely even smells of smoke anymore; he smells of thin air and nothingness, of oblivion. Only the zuoren collar, crossed left over right against his throat, still remains unfaded. It’s plain unrelenting, this immortal reminder of mortality.

Piggy decides to take this as a sign that the time has come, at long last. “I will be the new Guardian of this library,” he tells the boy, gentle yet resolute. “You’ve looked after it for so long, alone; you must be exhausted.” On an emboldened impulse, he leans forward and grasps the boy’s hands in his own. They’re cold and tremulous, and soft as a dying whisper. “I will return. You can rest soon. So wait for me, just a little longer. Trust me.”

For a long moment, all is silent within the Ghost Library. And then, finally, the guardian of the Ghost Library smiles, and it’s like the sun has broken through the smoke-stuffed clouds at last. It’s brighter than gold, brighter than fire, brighter than the singing stars. It’s the first time Piggy has ever seen him smile; perhaps it’s the first time he’s smiled in two thousand years. He looks like a young man, he looks like a child, he looks alive. He looks like he’s finally at peace, he looks like he’s finally ready.

“Alright,” says the boy, simply. There is a light within his face, pure and passionate, and Piggy wants to burn the image forever into his memory. It’s the most beautiful sight he’s ever had the fortune to witness. “I will.”

Mao Zedong dies in 1976, and all of China laments the loss of their Great Red Sun. He was 82. Piggy survives the countryside, powers through the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, and far outlives that age out of sheer spite.

Mao allegedly leaves a note to his so-called successor, Hua Guofeng, reading: “Ni ban shi, wo fang xin.” With you in charge, I’m at ease. Mao’s widowed wife, Jiang Qing, and his other so-called successors, the Gang of Four, strongly contest Hua over this, and then proceed to get arrested. Hua then proceeds to dilly-dally around, determined to do whatever Mao would have done (which becomes known as the Two Whatevers) until another one of Mao’s so-called successors, Deng Xiaoping, makes a stunning comeback from his own reeducation in exile and begins to push for reform. China finally gets its shit together—for the most part—and in 1981, the Chinese Communist Party passes an official proclamation that the Cultural Revolution was a huge fuckup on their part. Historians can’t agree on a single death toll, but some estimates rack up to as many as two million.

China is an ancient country with a written history of over 3,500 years. Much of it is lost forever. (Apparently, the Chinese government never sanctioned the destruction of historical relics; in fact, they’ve always endorsed the protection of China’s rich cultural heritage. This ensures that, in history books, all the blame falls on the Red Guards.) In any case, people soon return to their senses, which ushers in a new era called Boluan Fanzheng, Setting Things Right, in which they all try their damned hardest to un-fuck everything up. Old things are precious again, and ancient libraries and museums and temples and shrines and tombs are protected and preserved once more. What survived lives on.

Piggy, too, lives on. He spends the prime of his youth laboring away in the middle of nowhere. People like him are known as zhiqing, or sent-down youth. Most of them never have the opportunity to attend college; they marry local villagers and settle down permanently in their new rural homes, abandoning their old homes and families and identities forever. Many others can’t adapt to the hard conditions, and die. A lucky few make it out and go on to become authors—the genre of scar literature arises, wherein writers detail the profound suffering experienced during the Cultural Revolution—and enjoy prolific careers as scholars and intellectuals and artists, enjoy renown and acclamation.

In time, Piggy fulfills his promise and returns to the Ghost Library. He never sees the boy again; the boy is no more. (Yi lu hao zou, Piggy thinks to himself. Have a safe journey.) Piggy is the new Guardian now, and he dedicates his life to books: preserving the old and collecting the new. He collects literature, publishes essays and memoirs, and gives public speeches; he teaches the younger generations the lessons his own learned so painfully, so bloodily. He hopes that history will not repeat itself, hopes that no book will ever be burned again, hopes that someday he can find a new Guardian and rest, at long last. He hopes, he hopes, and he is not afraid.

When Piggy meets others, he finds that many of his fellow Chinese citizens, too, had stolen and smuggled and safeguarded what they could while the Cultural Revolution raged on. He makes friends, not comrades, and with them he forms a fired-forged camaraderie stronger than anyone’s hearts could have held during Mao Zedong’s reign of terror. (Someday, they will each be able to hear that man’s name without thinking, He is the Great Red Sun!) He meets a brilliant computer engineer who biked around the blood-stained streets in broad daylight with scraps of science textbook pages stashed inside his backpack, right under the rebels’ noses. He meets a renowned erhu player who smuggled home a radio and secretly tuned in to late-night news broadcasted live from Taiwan, illegal information from a government the Chinese Communist Party still refuses to recognize. He meets a famous children’s books author who copied entire novels from classical Western literature by hand so she could read them beneath her blankets, far less afraid of the dark than of what would happen if they caught her. He meets men and women who immigrated to the United States, who have foreign addresses and foreign names and foreign roots, whose children will know nothing of China but to boast of its cuisine, doll up and don cheongsams on holidays, listen to the lilting cadences of their parents’ mother tongue without understanding—and they will know nothing of the Cultural Revolution but what they are taught of it.

Piggy finds others, and others find him. Together they remember, they commemorate; they must not forget. They are scarred, but they are not broken. They watch as China rebuilds itself in the aftermath of its self-destruction, scabs over the wounds whose scars will never truly fade. They hurt, and heal, and piece together their memories, the story of their generation. History becomes a disparate yet hauntingly beautiful melting pot of the past, present, and future.

Piggy is but a man. He knows this much. He knows that ghosts will always roam the streets, that blood will always stain the earth and its history and their collective conscience. The living are all grown now, and they’ve all done unspeakable things in the name of survival, and yet they live on. He knows that he will die someday, and he is not afraid.

For he knows that his Ghost Library—their Ghost Library—will live on.